The following interview originally appeared in Video Watchdog #31 and appears here through the kind courtesy of Tim and Donna Lucas of Video Watchdog and Peter Blumenstock who conducted the interview.

JEAN

ROLLIN

HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE!

|

![]() Rollin's

comeback, Les Deux Orphelines Vampires ("The

Two Vampire Orphans"), based on his own novel, was filmed last July on location

in Paris and New York. Filmed on a tight budget of $3,000,000 Francs (about

$700,000)--Rollin's most indulgent budget ever--the production was beset by

a comedy of errors. Star Tina Aumont, cast as "The Ghoul," reportedly arrived

on the set expecting to play a Gypsy Woman, wearing an appropriate costume and

having memorized appropriate lines, though no such character or dialogue appeared

in Rollin's script! Later, when the owner of a chain of French cinemas saw the

film's final cut and expressed interest in financing a small theatrical release

in Paris, Rollin and the exhibitor went out to a celebratory dinner. As they

dined, the first two reels of the workprint were stolen from Rollin's car (along

with his video camera)--killing the time-sensitive distribution deal, and necessitating

that the film's first 20m be re-edited from scratch! Despite these drawbacks,

the result is perhaps Rollin's most beautiful achievement--nostalgic, erotic,

and above all, charming in its imaginative flourish. It screened at MIFED this

past autumn, and is presently seeking international distribution.

Rollin's

comeback, Les Deux Orphelines Vampires ("The

Two Vampire Orphans"), based on his own novel, was filmed last July on location

in Paris and New York. Filmed on a tight budget of $3,000,000 Francs (about

$700,000)--Rollin's most indulgent budget ever--the production was beset by

a comedy of errors. Star Tina Aumont, cast as "The Ghoul," reportedly arrived

on the set expecting to play a Gypsy Woman, wearing an appropriate costume and

having memorized appropriate lines, though no such character or dialogue appeared

in Rollin's script! Later, when the owner of a chain of French cinemas saw the

film's final cut and expressed interest in financing a small theatrical release

in Paris, Rollin and the exhibitor went out to a celebratory dinner. As they

dined, the first two reels of the workprint were stolen from Rollin's car (along

with his video camera)--killing the time-sensitive distribution deal, and necessitating

that the film's first 20m be re-edited from scratch! Despite these drawbacks,

the result is perhaps Rollin's most beautiful achievement--nostalgic, erotic,

and above all, charming in its imaginative flourish. It screened at MIFED this

past autumn, and is presently seeking international distribution.

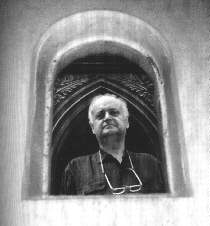

![]() The

following interview was conducted by Peter Blumenstock at Rollin's cozy, book-cluttered

apartment in Paris, in May 1995. -- Tim Lucas, Video Watchdog Magazine.

The

following interview was conducted by Peter Blumenstock at Rollin's cozy, book-cluttered

apartment in Paris, in May 1995. -- Tim Lucas, Video Watchdog Magazine.

Interview

by Peter Blumentstock:

How did you become interested in cinema?

![]() I

saw my very first film when I was about five years old, out in the country,

during the second World War. It made a profound impression on me. It was Capitaine

Fracasse (1942) by Abel Gance. I particularly remember the storm

sequence. I have never seen anything more fascinating and magical; it simply

changed my live forever. My mother told me that, after the screening, I said

I wanted to do exactly that when I grew up, so making films is a desire I've

carried around with me for quite some time now.

I

saw my very first film when I was about five years old, out in the country,

during the second World War. It made a profound impression on me. It was Capitaine

Fracasse (1942) by Abel Gance. I particularly remember the storm

sequence. I have never seen anything more fascinating and magical; it simply

changed my live forever. My mother told me that, after the screening, I said

I wanted to do exactly that when I grew up, so making films is a desire I've

carried around with me for quite some time now.

Where your parents happy about your choice of vocation?

The War years were a difficult time, when films were not commonly regarded as

respectable art form.

![]() Well,

you know how it is when children want to step into a certain profession. Nobody

believed this was more than a temporary idea. Also, my father was an actor working

in the theater, so that was also a heavy influence and helped. My parents were

separated. I never lived with my father, but once in awhile, I went to the theater

where he worked and saw him performing some of the classics on stage. Thus,

my wish to step into an artistic profession didn't appear to them as a curse.

Well,

you know how it is when children want to step into a certain profession. Nobody

believed this was more than a temporary idea. Also, my father was an actor working

in the theater, so that was also a heavy influence and helped. My parents were

separated. I never lived with my father, but once in awhile, I went to the theater

where he worked and saw him performing some of the classics on stage. Thus,

my wish to step into an artistic profession didn't appear to them as a curse.

When I was 15 years old, my mother gave me a typewriter, because she thought

it might be useful if I knew how to use one. That was an important moment; that's

when everything started. I found a means of expressing myself. I began to write

little screenplays and stories, heavily influenced by the films I saw. I adored

Cecil B. DeMille's work, and when I was about 13 or 14, I became really obsessed

with American serials. When I was a schoolboy, television didn't yet exist,

so after school, I regularly went to the movies with my friends. The cinema

and comic books were our whole lives! We were playing them, talking about them,

living them.

![]() I

remember JUNGLE JIM (1948) with Johnny Weissmuller,

also THE SHADOW (1940) and THE

MYSTERIOUS DR. SATAN (1940). These were serials, always to be continued

next week, so once an episode was over, nothing mattered but getting through

the next week as quickly as possible! The serials were not just a special piece

of culture; they also had a real spirit to them, which changed our lives and

attitudes. I certainly know, that these events are the source for most of the

ideas that recur throughout my films. The spirit, structure and contents of

the serial is the key to my type of cinema. I work from childhood memories,

and even if I sometimes cannot name a film in particular, I know that all my

ideas originated from that time.

I

remember JUNGLE JIM (1948) with Johnny Weissmuller,

also THE SHADOW (1940) and THE

MYSTERIOUS DR. SATAN (1940). These were serials, always to be continued

next week, so once an episode was over, nothing mattered but getting through

the next week as quickly as possible! The serials were not just a special piece

of culture; they also had a real spirit to them, which changed our lives and

attitudes. I certainly know, that these events are the source for most of the

ideas that recur throughout my films. The spirit, structure and contents of

the serial is the key to my type of cinema. I work from childhood memories,

and even if I sometimes cannot name a film in particular, I know that all my

ideas originated from that time.

Can you trace some specific examples?

![]() The

beach, for instance. That's a motif often seen in my films. I don't know exactly

where I saw it first, but I am sure it was in one of these serials. The whole

beginning of Les Demoniaques (1973), for

example, is a strange remembrance of the pirate and swashbuckler films I saw

back then.

The

beach, for instance. That's a motif often seen in my films. I don't know exactly

where I saw it first, but I am sure it was in one of these serials. The whole

beginning of Les Demoniaques (1973), for

example, is a strange remembrance of the pirate and swashbuckler films I saw

back then.

It's strange: most people directing or writing in

the genre also work from childhood memories, but they usually don't have nice

stories to tell. They seem to have experienced awful things as a child, which

is the reason why they chose the genre as their medium.

![]() My

childhood was wonderful, and my reflections of it are very romantic, sweet and

utterly transfigured. Like recalling one's first love, 20 years later.

My

childhood was wonderful, and my reflections of it are very romantic, sweet and

utterly transfigured. Like recalling one's first love, 20 years later.

What were your first actual steps toward working professionally

in the cinema?

![]() When

I was about 16 years old, I found a job at Le Films des Saturne. I was just

there to help, to write invoices and so forth, because I wanted to earn some

money and I certainly wanted to do something connected with cinema. They specialized

in creating opening and closing titles and little cartoons, but they also shot

real films, industrial shorts and documentaries now and then. One day, they

were assigned to make a short documentary about Snecma, a big factory in France

which builds motors for airplanes. I was part of the crew, so we went to the

factory and started shooting. It was my first time on a real movie set with

a camera and objects to be filmed. Of course, it had no actors, no fictional

story to tell, but it was enough to get me completely excited. It was a new

world for me. I remember working very hard, although it didn't seem to be work

for me. I did everything: I arranged the travelling shots, laid the tracks,

checked the electricity, helped the cameraman.

When

I was about 16 years old, I found a job at Le Films des Saturne. I was just

there to help, to write invoices and so forth, because I wanted to earn some

money and I certainly wanted to do something connected with cinema. They specialized

in creating opening and closing titles and little cartoons, but they also shot

real films, industrial shorts and documentaries now and then. One day, they

were assigned to make a short documentary about Snecma, a big factory in France

which builds motors for airplanes. I was part of the crew, so we went to the

factory and started shooting. It was my first time on a real movie set with

a camera and objects to be filmed. Of course, it had no actors, no fictional

story to tell, but it was enough to get me completely excited. It was a new

world for me. I remember working very hard, although it didn't seem to be work

for me. I did everything: I arranged the travelling shots, laid the tracks,

checked the electricity, helped the cameraman.

I've also heard that you worked as an editor in the

French army?

![]() That's

correct. When I did my military service, I worked in the cinema department together

with Claude Lelouch, who had to join the army at the same time as I did. We

worked on army commercials there. He directed and I did the montage. We did

two films. One was a documentary about the mechanographic service called

Mechanographie; the other was a real film running

one hour, with actors and a story, called La Guerre

de Silence ("The War of Silence").

That's

correct. When I did my military service, I worked in the cinema department together

with Claude Lelouch, who had to join the army at the same time as I did. We

worked on army commercials there. He directed and I did the montage. We did

two films. One was a documentary about the mechanographic service called

Mechanographie; the other was a real film running

one hour, with actors and a story, called La Guerre

de Silence ("The War of Silence").

It's hard to believe that you started as an editor.

When I look at your films today, I never see montage being asserted as a stylistic

device.

![]() For

me, montage is just a means to combine scenes, nothing more. I think the creation

of a film should happen during the shooting. Since I began in this business

as an editor, I know exactly where I want to have a cut, so I usually edit my

films in camera. Later on, the editing process is just a formality for me. The

scenes are shot in a certain way and it is impossible to arrange them differently.

I never use a lot of cameras and shoot scenes from a variety of different angles

to choose from afterwards. I hate that. For me, the creation of cinema should

occur during the writing and shooting stage. Afterwards, we can re-arrange a

bit here and there, sure, but that's about it. Also, from a stylistic point

of view, the montage not particularly important to me. I very much prefer long

scenes and plateaus. Editing is something completely abstract; it adds another

dimension to the story which I don't really care about. I have chosen different

ways, so for me, the editing is basically nothing but a reflection of the shooting

process.

For

me, montage is just a means to combine scenes, nothing more. I think the creation

of a film should happen during the shooting. Since I began in this business

as an editor, I know exactly where I want to have a cut, so I usually edit my

films in camera. Later on, the editing process is just a formality for me. The

scenes are shot in a certain way and it is impossible to arrange them differently.

I never use a lot of cameras and shoot scenes from a variety of different angles

to choose from afterwards. I hate that. For me, the creation of cinema should

occur during the writing and shooting stage. Afterwards, we can re-arrange a

bit here and there, sure, but that's about it. Also, from a stylistic point

of view, the montage not particularly important to me. I very much prefer long

scenes and plateaus. Editing is something completely abstract; it adds another

dimension to the story which I don't really care about. I have chosen different

ways, so for me, the editing is basically nothing but a reflection of the shooting

process.

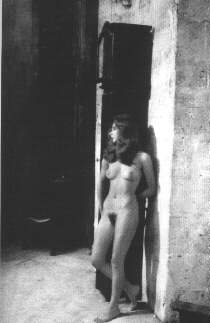

Beautiful Sandra Julien in Le Frisson Des Vampires |

In 1958, you directed your first short film,

Les Amours Jaunes ("The Yellow

Lovers"). How did that happen? |

![]() I

did my next short film in 1961. It was called Ciel

de Cuivre ("Sky of Copper"). It was quite surreal, telling

a sentimental story; unfortunately, it wasn't very good. I never finished it

because I ran out of money, and also because I realized it wasn't really working

out. The footage is now lost. I have no idea where it might be.

I

did my next short film in 1961. It was called Ciel

de Cuivre ("Sky of Copper"). It was quite surreal, telling

a sentimental story; unfortunately, it wasn't very good. I never finished it

because I ran out of money, and also because I realized it wasn't really working

out. The footage is now lost. I have no idea where it might be.

One year later, you worked for the first (and also

last) time as an assistant director. The film was Jean-Marc Thibault's Un

Cheval pour Deux ("A Horse for Two," 1962).

![]() That

was not a particularly pleasant experience. I don't think I am a very good assistant

[LAUGHS]; I think it was enough to take this job only once. I came back from

the army, I was just married, and I needed work to make a living. Some friends

of mine were running a theatre at Montmatre, and they were also involved in

producing films once in awhile. One day, they asked if I was interested in assisting

Thibault and I agreed. I learned a lot of things on the set. Nevertheless, it

was an experience which may have influenced my decision to approach cinema in

a different way. I am basically a self-taught filmmaker. Sure, I worked as an

editor, but everything else I know about making films comes from doing it. Improvising,

trying things, making mistakes and trying to make it better next time. It is

an instinctive process for me. I have never seen the inside of a film school

in my entire life. I think I know how a traditional, classical film should be

shot, what technique is required, but when I shot my first films, I tried to

forget about that as much as possible. I wanted to work spontaneously, without

any regulations in my head. I don't believe there is only one form of cinema,

just because it has become the standard approach, and because most films are

shot that way. That's an unnecessary limitation.

That

was not a particularly pleasant experience. I don't think I am a very good assistant

[LAUGHS]; I think it was enough to take this job only once. I came back from

the army, I was just married, and I needed work to make a living. Some friends

of mine were running a theatre at Montmatre, and they were also involved in

producing films once in awhile. One day, they asked if I was interested in assisting

Thibault and I agreed. I learned a lot of things on the set. Nevertheless, it

was an experience which may have influenced my decision to approach cinema in

a different way. I am basically a self-taught filmmaker. Sure, I worked as an

editor, but everything else I know about making films comes from doing it. Improvising,

trying things, making mistakes and trying to make it better next time. It is

an instinctive process for me. I have never seen the inside of a film school

in my entire life. I think I know how a traditional, classical film should be

shot, what technique is required, but when I shot my first films, I tried to

forget about that as much as possible. I wanted to work spontaneously, without

any regulations in my head. I don't believe there is only one form of cinema,

just because it has become the standard approach, and because most films are

shot that way. That's an unnecessary limitation.

L'Itineraire Marin (1960)

was supposed to become your first feature film. You also had to abandon that

project.

![]() We

shot one hour of usable film. Then we ran into some problems and needed professional

help to shoot the remaining thirty minutes. I was looking for money and the

possibility of a small distribution. I saw every professional working in the

film business in Paris, but nobody cared. Marguerite Duras worked with me on

that film. She was completely unknown at that time. Nowadays, that's certainly

different [LAUGHS]! Then there was also Gaston Modot, who appeared in L'Age

d'Or, and Ren-Jacques Chauffard. The negative is in the lab, so

maybe, one day, I will dig it out and do something with it. Perhaps a small

video release. Michel Lagrange, one of the actors, has since become a well known

writer. He died a few months ago and some people want to resurrect my film because

of him.

We

shot one hour of usable film. Then we ran into some problems and needed professional

help to shoot the remaining thirty minutes. I was looking for money and the

possibility of a small distribution. I saw every professional working in the

film business in Paris, but nobody cared. Marguerite Duras worked with me on

that film. She was completely unknown at that time. Nowadays, that's certainly

different [LAUGHS]! Then there was also Gaston Modot, who appeared in L'Age

d'Or, and Ren-Jacques Chauffard. The negative is in the lab, so

maybe, one day, I will dig it out and do something with it. Perhaps a small

video release. Michel Lagrange, one of the actors, has since become a well known

writer. He died a few months ago and some people want to resurrect my film because

of him.

The Nouvelle Vague became extremely popular at that

time. Am I right to suspect that you were never really a follower of that movement?

What was your attitude towards these directors and their cinema?

![]() I

met most of them at Henri Langlois' Cinemateque Francaise; we talked, and I

saw their films, but you're right. It was not exactly my cup of tea. It was

a movement similar to German New Wave filmmaking, some sort of rebellion against

the old directors--not only their approach and vision, but also their technical

style. I was always most attracted to traditional, old French cinema, but there

is no doubt that the Nouvelle Vague played an important economic role. They

proved it was possible for young people without experience to make successful,

acclaimed films on a small budget. They gave me and others the courage to attempt

the same feat.

I

met most of them at Henri Langlois' Cinemateque Francaise; we talked, and I

saw their films, but you're right. It was not exactly my cup of tea. It was

a movement similar to German New Wave filmmaking, some sort of rebellion against

the old directors--not only their approach and vision, but also their technical

style. I was always most attracted to traditional, old French cinema, but there

is no doubt that the Nouvelle Vague played an important economic role. They

proved it was possible for young people without experience to make successful,

acclaimed films on a small budget. They gave me and others the courage to attempt

the same feat.

In the early '60s, you also became interested in politics.

You did a short documentary about Generalissimo Francisco Franco called Vivre

en Espagne ("Life in Spain," 1964). How come you chose a Spaniard as

your target?

![]() I

was part of the "left wing" at that time, and there was an organization here

in France to help the Spanish resistance against Franco. I knew them, and they

asked me to make a short documentary, shot in Spain. I was interested, so we

packed our camera equipment and went there. The resulting film, about thirty

minutes, wasn't very good, but we risked a great deal to get it made. There

was another French crew shooting risky stuff in Madrid at that time; Frdric

Rossif was making Mourir

Madrid ("Death

in Madrid," 1964). I don't know which company blew their cover first, but we

suddenly found ourselves hunted by the police and we managed to cross the border

back into France just in time. It was close, very close [LAUGHS]!

I

was part of the "left wing" at that time, and there was an organization here

in France to help the Spanish resistance against Franco. I knew them, and they

asked me to make a short documentary, shot in Spain. I was interested, so we

packed our camera equipment and went there. The resulting film, about thirty

minutes, wasn't very good, but we risked a great deal to get it made. There

was another French crew shooting risky stuff in Madrid at that time; Frdric

Rossif was making Mourir

Madrid ("Death

in Madrid," 1964). I don't know which company blew their cover first, but we

suddenly found ourselves hunted by the police and we managed to cross the border

back into France just in time. It was close, very close [LAUGHS]!

It is curious, because you never really approached

an openly political subject afterwards in your fantastic films, which are normally

predestined to contain certain political ideas.

![]() Well,

the fantastic cinema is always a good vehicle for discussing certain political

ideas in the form of symbols and metaphoras, but you're right, I have never

really worked with political themes afterwards. Although now that you mention

it, I remember that, when La Nuit des Traques

("Night of the Hunted," 1980) opened here in Paris, a lot of people came to

me and said I had made a film about the German prison problem. I am talking

about Stammheim and the RAF. Looking back, I think it might be true. I didn't

do it consciously, but it was the same period, so it is absolutely possible.

You know, those stories about solitary confinement, no light, nobody to talk

to, no noises, everything very cold and sterile, and this is exactly what people

saw in my film. Perhaps I was influenced to bring that to the screen.

Well,

the fantastic cinema is always a good vehicle for discussing certain political

ideas in the form of symbols and metaphoras, but you're right, I have never

really worked with political themes afterwards. Although now that you mention

it, I remember that, when La Nuit des Traques

("Night of the Hunted," 1980) opened here in Paris, a lot of people came to

me and said I had made a film about the German prison problem. I am talking

about Stammheim and the RAF. Looking back, I think it might be true. I didn't

do it consciously, but it was the same period, so it is absolutely possible.

You know, those stories about solitary confinement, no light, nobody to talk

to, no noises, everything very cold and sterile, and this is exactly what people

saw in my film. Perhaps I was influenced to bring that to the screen.

![]() In

general, the fantastic cinema is always political, because it is always in the

opposition. It is subversive and it is popular, which means it is dangerous.

I made films with sex and violence at a time when censorship was very strong,

so that was certainly a political statement as well, although again, not a conscious

one. I just happen to have an imagination which doesn't correspond with those

of certain conservative people [LAUGHS]!

In

general, the fantastic cinema is always political, because it is always in the

opposition. It is subversive and it is popular, which means it is dangerous.

I made films with sex and violence at a time when censorship was very strong,

so that was certainly a political statement as well, although again, not a conscious

one. I just happen to have an imagination which doesn't correspond with those

of certain conservative people [LAUGHS]!

Around the time of your Franco documentary, you also

started publishing fiction. In which literary style would you classify your

writing?

![]() I

don't know. I cannot really mention any specific authors which have influenced

my style particularly. Sure, I adore Gaston Leroux and Corbiere, but they did

not affect my writing on a stylistic level. I began writing books the way I

was writing scripts. I am a very visual person, thus also a very visual writer.

In films, I have something to show; in books, I want to convey the same thing,

a world seen through my eyes, so I have to express the same vision with words.

My books often appear like screenplays and they share the same rhythm and structure

as my films.

I

don't know. I cannot really mention any specific authors which have influenced

my style particularly. Sure, I adore Gaston Leroux and Corbiere, but they did

not affect my writing on a stylistic level. I began writing books the way I

was writing scripts. I am a very visual person, thus also a very visual writer.

In films, I have something to show; in books, I want to convey the same thing,

a world seen through my eyes, so I have to express the same vision with words.

My books often appear like screenplays and they share the same rhythm and structure

as my films.

So do you think of yourself as a director who writes,

or as a writer who directs films?

![]() It

depends. I am not in the same state of mind when I write and when I make a film.

I am, of course, much freer when I write, because I don't have to bother about

anything. I just need paper and a typewriter. The creation is not the same,

at least not when it comes to my kind of cinema. With a film, you have to consider

that there are actors, who often don't want the same things you want; there

are technicians, money problems, a producer, and you have to fight with all

these elements. On a book, I only have to fight with my imagination. The visual

world is much more open to surrealism and metaphysics. Cinema is a wonderful

medium to express navet and vagueness. And it is an adventure, where you just

delve deeply into it and get carried away by the events and problems. The resulting

film is a combination of yourself, your luck, your misfortune, your problems

and your subconscious.

It

depends. I am not in the same state of mind when I write and when I make a film.

I am, of course, much freer when I write, because I don't have to bother about

anything. I just need paper and a typewriter. The creation is not the same,

at least not when it comes to my kind of cinema. With a film, you have to consider

that there are actors, who often don't want the same things you want; there

are technicians, money problems, a producer, and you have to fight with all

these elements. On a book, I only have to fight with my imagination. The visual

world is much more open to surrealism and metaphysics. Cinema is a wonderful

medium to express navet and vagueness. And it is an adventure, where you just

delve deeply into it and get carried away by the events and problems. The resulting

film is a combination of yourself, your luck, your misfortune, your problems

and your subconscious.

![]() What

was important for me, however, was to stick to the theatrical concept of improvisation

in my books as well. It is the same journey with screenplays, books, or on the

set. I write something and suddenly, off the cuff, I can improvise ten or twenty

pages with things that just flood my mind.

What

was important for me, however, was to stick to the theatrical concept of improvisation

in my books as well. It is the same journey with screenplays, books, or on the

set. I write something and suddenly, off the cuff, I can improvise ten or twenty

pages with things that just flood my mind.

![]() I

don't know to which extent my work as a filmmaker has influenced my writings

and vice versa. That's something I might be able to tell you after I make my

next film, Les Deux Orphelines Vampires

("The Two Vampire Orphans"), because it will be based on one of my novels. It

will also be interesting for me, because I've been extremely busy with my writing

in recent years, and haven't directed a feature for quite some time. I think

a director who is also a writer pays attention to different details. That can

be dangerous, but it can also make for a very strange film--in the positive

sense. It is true that writing directors make films which are much more personal

and metaphysical, because cinema means that the writer must abandon one dimension.

In books, you can talk to the reader, you can write down people's thoughts.

Film is more vague; you know what the characters feel, and you try to convey

these emotions visually. Curiously, though I like to re-read my old books now

and again, I don't like looking back at my old films. I don't know why, really;

maybe because the fantasy in them has become fixed, which might have suited

my imagination then but not now, so I am disappointed. Cinema means to decide,

to decide which actor to use, which set, which camera angle, and to eliminate

all other possibilities in your head.

I

don't know to which extent my work as a filmmaker has influenced my writings

and vice versa. That's something I might be able to tell you after I make my

next film, Les Deux Orphelines Vampires

("The Two Vampire Orphans"), because it will be based on one of my novels. It

will also be interesting for me, because I've been extremely busy with my writing

in recent years, and haven't directed a feature for quite some time. I think

a director who is also a writer pays attention to different details. That can

be dangerous, but it can also make for a very strange film--in the positive

sense. It is true that writing directors make films which are much more personal

and metaphysical, because cinema means that the writer must abandon one dimension.

In books, you can talk to the reader, you can write down people's thoughts.

Film is more vague; you know what the characters feel, and you try to convey

these emotions visually. Curiously, though I like to re-read my old books now

and again, I don't like looking back at my old films. I don't know why, really;

maybe because the fantasy in them has become fixed, which might have suited

my imagination then but not now, so I am disappointed. Cinema means to decide,

to decide which actor to use, which set, which camera angle, and to eliminate

all other possibilities in your head.

France is renowned for its artistic and literary groups--the

Surrealists, the Nouvelle Vague, the Nouveau Roman, and so forth. I get the

impression that you formed something like that with people like Ado Kyrou and

Eric Losfeld. Many of these people came to the library of Eric Losfeld.

![]() I

was one of them. I was very young and came to listen to what all those people

were saying during the meetings. I was sitting in one dark corner, quiet, and

listening. I remember Ado Kyrou there, and Losfeld and Jacques Sternberg. One

day, Losfeld looked at me and ordered me to come over to get into a conversation

with them. That was the beginning. I was so proud to be there, to be able to

speak with all these people, who were my heroes. Ado Kyrou was a very respected

and important critic at that time. I read everything he wrote. We became close

friends, and I came every Saturday morning to the library to meet with them.

For me, they represented the spirit of everything. They were incredibly cultured,

and they shared the same attitude towards life as I did. We were of the same

kind. I agreed with everything they said, everything they wrote rang true for

me. When I was among them, I felt at home and understood.

I

was one of them. I was very young and came to listen to what all those people

were saying during the meetings. I was sitting in one dark corner, quiet, and

listening. I remember Ado Kyrou there, and Losfeld and Jacques Sternberg. One

day, Losfeld looked at me and ordered me to come over to get into a conversation

with them. That was the beginning. I was so proud to be there, to be able to

speak with all these people, who were my heroes. Ado Kyrou was a very respected

and important critic at that time. I read everything he wrote. We became close

friends, and I came every Saturday morning to the library to meet with them.

For me, they represented the spirit of everything. They were incredibly cultured,

and they shared the same attitude towards life as I did. We were of the same

kind. I agreed with everything they said, everything they wrote rang true for

me. When I was among them, I felt at home and understood.

![]() Eric

Losfeld intended to publish my first novel, LES PAYS LOINS ("The Distant Lands"),

which never happened because he died. I had two things going with Losfeld. First,

he wanted to publish this novel of mine, then, there was this strange French

writer named George Maxwell, who wrote a series of 22 very bizarre books, and

Losfeld had the rights, so we wanted to reprint them with an introduction by

myself. I was also supposed to do the cover photographies.

Eric

Losfeld intended to publish my first novel, LES PAYS LOINS ("The Distant Lands"),

which never happened because he died. I had two things going with Losfeld. First,

he wanted to publish this novel of mine, then, there was this strange French

writer named George Maxwell, who wrote a series of 22 very bizarre books, and

Losfeld had the rights, so we wanted to reprint them with an introduction by

myself. I was also supposed to do the cover photographies.

In 1965, you made a short film called Les Pays Loins.

Did you do it because the book was never published?

![]() No,

no. I just used the title. The story got nothing to do with my novel, which

was basically written in the form of an essay.

No,

no. I just used the title. The story got nothing to do with my novel, which

was basically written in the form of an essay.

In 1967, you also got involved in comics. I am talking

about SAGA OF XAM.

![]() Eric

Losfeld had published the first adult comic in France, BARBARELLA by Jean-Claude

Forest. It was extremely successful, so he wanted to publish more adult comics.

One of my friends was Nicolas Deville, and he was responsible for the decoration

of some of my short films. We were very close, and I knew that he was a fabulous

painter. I encouraged him to propose something to Losfeld, so I arranged a meeting

and it worked out. We did SAGA OF XAM together. It was a little science fiction

story about a girl from outer space coming down to earth to experience a lot

of strange adventures. I also met Philippe Druillet around the same time. He

would later play in Le Viol du Vampire ("Rape

of the Vampire," 1967) and created the posters for some of my films.

Eric

Losfeld had published the first adult comic in France, BARBARELLA by Jean-Claude

Forest. It was extremely successful, so he wanted to publish more adult comics.

One of my friends was Nicolas Deville, and he was responsible for the decoration

of some of my short films. We were very close, and I knew that he was a fabulous

painter. I encouraged him to propose something to Losfeld, so I arranged a meeting

and it worked out. We did SAGA OF XAM together. It was a little science fiction

story about a girl from outer space coming down to earth to experience a lot

of strange adventures. I also met Philippe Druillet around the same time. He

would later play in Le Viol du Vampire ("Rape

of the Vampire," 1967) and created the posters for some of my films.

Maurice Lemethre & Jean Rollin on the set of La Vampire Nue. |

Around this time, you wrote a lengthy

essay about Gaston Leroux which appeared in the final two issues of the

famous magazine MIDI-MINUIT FANTASTIQUE. |

How did you meet Sam Selsky, the producer of most

of your subsequent films?

![]() Selsky

is a European American, so to speak; he's lived in France for a long time. He

has been to every corner in the world, but eventually ended up in Paris, working

as an administrator for UNESCO. He loved the cinema, so one day, he bought a

little movie theatre and also got into production. I doubt that he otherwise

would have touched the project. I don't know why he chose to work with me. Just

a good feeling maybe. He trusted me, and he was the first one to do so. At that

time, I was trying to raise money for films, but nobody gave me a chance because

I had no real experience. Selsky believed in me. Also, it was just half an hour

of film, so it was not too much of a financial risk, and I managed to convince

him. And then he said, like a perfect businessman, that if we could make half

an hour of film for practically nothing, we could also make a feature-length

film for practically nothing-- knowing that it was preferable to have a complete

feature in hand rather than a short. There was also the consideration that my

friend, the distributor, at that particular moment, was broke and that our 30

minute film might never see the light of day because of that. Thus, we had to

add a second part to Le Viol du Vampire,

entitled La Reine des Vampires ("Queen

of the Vampires"). Selsky, who is quite a materialistic person, said that the

film was so strange, so absurd, it was possible that audiences would like it.

He understood absolutely nothing of the story, but it was so bizarre he believed

it could be successful. And he was right, it made quite some money.

Selsky

is a European American, so to speak; he's lived in France for a long time. He

has been to every corner in the world, but eventually ended up in Paris, working

as an administrator for UNESCO. He loved the cinema, so one day, he bought a

little movie theatre and also got into production. I doubt that he otherwise

would have touched the project. I don't know why he chose to work with me. Just

a good feeling maybe. He trusted me, and he was the first one to do so. At that

time, I was trying to raise money for films, but nobody gave me a chance because

I had no real experience. Selsky believed in me. Also, it was just half an hour

of film, so it was not too much of a financial risk, and I managed to convince

him. And then he said, like a perfect businessman, that if we could make half

an hour of film for practically nothing, we could also make a feature-length

film for practically nothing-- knowing that it was preferable to have a complete

feature in hand rather than a short. There was also the consideration that my

friend, the distributor, at that particular moment, was broke and that our 30

minute film might never see the light of day because of that. Thus, we had to

add a second part to Le Viol du Vampire,

entitled La Reine des Vampires ("Queen

of the Vampires"). Selsky, who is quite a materialistic person, said that the

film was so strange, so absurd, it was possible that audiences would like it.

He understood absolutely nothing of the story, but it was so bizarre he believed

it could be successful. And he was right, it made quite some money.

![]() Of

course, it was also a terrible scandal. After the film had opened in four Paris

cinemas to very extreme audience reactions, I said I would never make another

film. I absolutely didn't expect this reaction; it hit me like a bolt from the

blue! People were shouting, throwing trash at the screen. The press went crazy

and called me a madman, they called the film the work of a group of crazy students!

I was really afraid they are going to lynch me. Some members of the cast and

crew freaked out, as well. They hated it, and shouted at me as if I had committed

a crime. And I didn't realize at all what I had done after shooting. Now, when

I see the film again, I realize how crazy it was to do something like that at

this moment in time, with all the student riots in the streets of Paris. It

is very much a film of its time, although I never wanted it to be like that

and I didn't realize it back then. I know now that my environment influences

me a great deal, even if I'm not aware of it, which is also the reason why I

told you that story of Stammhaim. I really think there could be a connection,

just as there is a connection between Le Viol...

and its time of creation.

Of

course, it was also a terrible scandal. After the film had opened in four Paris

cinemas to very extreme audience reactions, I said I would never make another

film. I absolutely didn't expect this reaction; it hit me like a bolt from the

blue! People were shouting, throwing trash at the screen. The press went crazy

and called me a madman, they called the film the work of a group of crazy students!

I was really afraid they are going to lynch me. Some members of the cast and

crew freaked out, as well. They hated it, and shouted at me as if I had committed

a crime. And I didn't realize at all what I had done after shooting. Now, when

I see the film again, I realize how crazy it was to do something like that at

this moment in time, with all the student riots in the streets of Paris. It

is very much a film of its time, although I never wanted it to be like that

and I didn't realize it back then. I know now that my environment influences

me a great deal, even if I'm not aware of it, which is also the reason why I

told you that story of Stammhaim. I really think there could be a connection,

just as there is a connection between Le Viol...

and its time of creation.

![]() Sam

Selsky arranged a special screening for the Moulin brothers, the owners of the

Midi-Minuit, the Scarlett and some other cinemas in the same mold. He knew that

it was impossible to understand what the hell was going on in the story, so

during the screening, he was constantly talking to them, disturbing their concentration.

So, whenever they said they couldn't understand why this-or-that happened, Selsky

replied that they had missed a very important plot twist because of his talking

and that they shouldn't worry because it made perfect sense! [LAUGHS]

Sam

Selsky arranged a special screening for the Moulin brothers, the owners of the

Midi-Minuit, the Scarlett and some other cinemas in the same mold. He knew that

it was impossible to understand what the hell was going on in the story, so

during the screening, he was constantly talking to them, disturbing their concentration.

So, whenever they said they couldn't understand why this-or-that happened, Selsky

replied that they had missed a very important plot twist because of his talking

and that they shouldn't worry because it made perfect sense! [LAUGHS]

Would you say that Le Viol du Vampire was the most

improvisational of your films? <

![]() Yes,

that one, but also Les Trottoirs des Bangkok

("Streetwalkers of Bangkok," 1984). Some critics wrote that I made two films

in my career that are virtually identical: Le Viol...

and Les Trottoirs..., and they might be

right. When we did Le Viol..., I was quite

serious about it, but when I did Les Trottoirs...,

I took a tongue-in-cheek approach. But both films stem from the same love for

a certain type of cinema and both are definitely honest films. Even the soundtrack

of Le Viol... was improvised! Franois Tusques

was one of the very first French musicians to play free jazz and I adore jazz,

so it was clear I wanted that type of music for the film. You can see Franois

together with his group in the theatre sequence. We shot it in the Grand Guignol

theater during their final active period. I loved their work and I always wanted

to do something connected with them.

Yes,

that one, but also Les Trottoirs des Bangkok

("Streetwalkers of Bangkok," 1984). Some critics wrote that I made two films

in my career that are virtually identical: Le Viol...

and Les Trottoirs..., and they might be

right. When we did Le Viol..., I was quite

serious about it, but when I did Les Trottoirs...,

I took a tongue-in-cheek approach. But both films stem from the same love for

a certain type of cinema and both are definitely honest films. Even the soundtrack

of Le Viol... was improvised! Franois Tusques

was one of the very first French musicians to play free jazz and I adore jazz,

so it was clear I wanted that type of music for the film. You can see Franois

together with his group in the theatre sequence. We shot it in the Grand Guignol

theater during their final active period. I loved their work and I always wanted

to do something connected with them.

Was the vampire motif forced on you by the scenario

of DEAD MEN WALK?

![]() No,

that was a coincidence. Everybody knew I loved that type of film and that I

always wanted to shoot something like that.

No,

that was a coincidence. Everybody knew I loved that type of film and that I

always wanted to shoot something like that.

You are obviously fascinated by vampires. What makes

them so special for you? You never really cared about Frankenstein, werewolves

or mummies.

![]() That's

difficult to answer. I don't really know. Maybe, because the vampire can be

attractive, and certainly also because it gave me the possibility to show some

nice girls not wearing very much [LAUGHS]! An erotic werewolf or an erotic mummy...

I don't think so. Maybe it's also got something to do with my nature and the

nature of my films. A vampire is like an animal, a predator-- wild, emotional,

naive, primitive, sensual, not too concerned with logic, driven by emotions,

but also very aesthetic and beautiful, and these are terms also often used when

my films are being described. At least when they are being described by my admirers

[LAUGHS]!

That's

difficult to answer. I don't really know. Maybe, because the vampire can be

attractive, and certainly also because it gave me the possibility to show some

nice girls not wearing very much [LAUGHS]! An erotic werewolf or an erotic mummy...

I don't think so. Maybe it's also got something to do with my nature and the

nature of my films. A vampire is like an animal, a predator-- wild, emotional,

naive, primitive, sensual, not too concerned with logic, driven by emotions,

but also very aesthetic and beautiful, and these are terms also often used when

my films are being described. At least when they are being described by my admirers

[LAUGHS]!

Since Le Viol du Vampire,

you have been stereotyped as a director of erotic vampire films. Are you happy

with that?

![]() Honestly,

I don't care. Some people say I'm a genius, others consider me the greatest

moron who ever stepped behind a camera. I have heard so many things said about

me and my films, but these are just opinions. I am perfectly happy with what

I do, because it has always been my choice.

Honestly,

I don't care. Some people say I'm a genius, others consider me the greatest

moron who ever stepped behind a camera. I have heard so many things said about

me and my films, but these are just opinions. I am perfectly happy with what

I do, because it has always been my choice.

|

La Vampire Nue

("The Nude Vampire," 1969) was your first color film. The animal masks

in it are very reminiscent of Franju's Judex. |

Les Demoniaques |

La Vampire Nue was your

first collaboration with the twins Catherine and Marie-Pierre "Pony" Castel,

who became regulars in your subsequent works.

![]() Oh

yes! They are the only twins to be found in French cinema, and they've done

vampire films and porn together [LAUGHS]! They were originally hairdressers.

One of my assistants came to me one day and told me that he'd found a pair of

twins who might interest me, so I met with them. They wanted to be actresses,

a dream they had for quite some time. They had a certain nave quality that

I felt would be ideal for my type of cinema. It was very difficult to get the

two of them at the same time. Originally, I wanted to have them both in Le

Frisson..., but one of them [Marie-Pierre] was pregnant, so we could

use only one and had to find that beautiful Asian substitute for the other.

After Requiem pour un Vampire ("Requiem

for a Vampire," 1971), the other one [Catherine] got pregnant, so once again

there was a problem! I don't know whatever became of them. One of them was living

not far from here, but I haven't seen her for quite some time now.

Oh

yes! They are the only twins to be found in French cinema, and they've done

vampire films and porn together [LAUGHS]! They were originally hairdressers.

One of my assistants came to me one day and told me that he'd found a pair of

twins who might interest me, so I met with them. They wanted to be actresses,

a dream they had for quite some time. They had a certain nave quality that

I felt would be ideal for my type of cinema. It was very difficult to get the

two of them at the same time. Originally, I wanted to have them both in Le

Frisson..., but one of them [Marie-Pierre] was pregnant, so we could

use only one and had to find that beautiful Asian substitute for the other.

After Requiem pour un Vampire ("Requiem

for a Vampire," 1971), the other one [Catherine] got pregnant, so once again

there was a problem! I don't know whatever became of them. One of them was living

not far from here, but I haven't seen her for quite some time now.

You are basically the only director in France making

genre films. Whenever French fantasy cinema is mentioned, your name is always

dropped as well. Do you think your films can be seen as proper examples of French

fantastic culture?

![]() I

don't think it can be said that I am a representative of French fantastic culture

per se. My films are melting pots of American pulp films and a certain amount

of German Expressionism. I was definitely influenced by the Expressionist films

of Robert Wiene. Not necessarily THE CABINET OF DR.

CALIGARI, but I remember THE HANDS OF ORLAC.

All that, and of course the films of the great period of British filmmaking

and many other things I cannot name because I don't consciously realize how

much they influenced me. Also, there is certainly a heavy dose of my own personality

involved. I am French, so there are certainly a lot of French things to be found

in them. It is not particularly French culture, it is particularly Rollin [LAUGHS]!

I

don't think it can be said that I am a representative of French fantastic culture

per se. My films are melting pots of American pulp films and a certain amount

of German Expressionism. I was definitely influenced by the Expressionist films

of Robert Wiene. Not necessarily THE CABINET OF DR.

CALIGARI, but I remember THE HANDS OF ORLAC.

All that, and of course the films of the great period of British filmmaking

and many other things I cannot name because I don't consciously realize how

much they influenced me. Also, there is certainly a heavy dose of my own personality

involved. I am French, so there are certainly a lot of French things to be found

in them. It is not particularly French culture, it is particularly Rollin [LAUGHS]!

![]() It's

very difficult to answer that question, you know, because there isn't really

a French tradition of fantastic cinema. I guess what you mean is that certain

cultural bond that exists within a country's cinema, such as the reflection

of the Weimar Republic and the early shades of Fascism in German Expressionist

cinema, or Catholicism in the Italian cinema, right?

It's

very difficult to answer that question, you know, because there isn't really

a French tradition of fantastic cinema. I guess what you mean is that certain

cultural bond that exists within a country's cinema, such as the reflection

of the Weimar Republic and the early shades of Fascism in German Expressionist

cinema, or Catholicism in the Italian cinema, right?

Exactly.

![]() Well,

as far as France is concerned, I would have to name literature as the basis

of our fantastic culture. The French cinema, as a rule, is not fantastic. There

are no roots. Also, I don't think French people in general like the fantastic,

at least not what I consider to be fantastic. Sure, we have a couple of magazines

dedicated to horror films, but they survive because they print gory stills and

that's what attracts people. These are two different pairs of shoes for me.

Well,

as far as France is concerned, I would have to name literature as the basis

of our fantastic culture. The French cinema, as a rule, is not fantastic. There

are no roots. Also, I don't think French people in general like the fantastic,

at least not what I consider to be fantastic. Sure, we have a couple of magazines

dedicated to horror films, but they survive because they print gory stills and

that's what attracts people. These are two different pairs of shoes for me.

It was obvious from your early films that you weren't

at all concerned with popular trends and did pretty much your own thing. That's

also the case when you made more "commercial" horror films such as Les

Raisins de la Mort ("The Grapes of Death," 1978) or La

Morte Vivante ("The Living Dead Girl," 1982). Did you always intend to

remain a maverick, an outsider to the French film industry, or did you have

hopes of breaking into more commercial areas of the film business?

![]() I

don't think it could have worked, and I realized that. I knew I had to remain

in my parallel world, because anything else would have resulted in a disaster.

The films I make are impossible with a normal production. They have to be marginal.

I certainly was tempted to try to make a big film with big stories and big stars,

but I'm not sure I could make a good film like that. You know, Bunuel was a

bit like that. When he had to shoot a little film with no money and no professional

actors, somewhere in the desert, like NAZARIN,

he managed to create a masterpiece. When he had a reasonable budget, the result

was not exactly the same. Maybe we share the same kind of imagination. My imagination

is too strong to completely abandon what is important to me. Also, I don't think

I am a universal director. I don't think I could direct comedies, for example.

I simply cannot escape from myself. I have to fight with the money, that's better

for me, that's the type of cinema I grew up with. The difficulties I encounter

during production oblige me to invent, to become really creative. I think it's

in these moments that my cinematic universe becomes a reality. Anything else

would be dishonest and a waste of time and energy.

I

don't think it could have worked, and I realized that. I knew I had to remain

in my parallel world, because anything else would have resulted in a disaster.

The films I make are impossible with a normal production. They have to be marginal.

I certainly was tempted to try to make a big film with big stories and big stars,

but I'm not sure I could make a good film like that. You know, Bunuel was a

bit like that. When he had to shoot a little film with no money and no professional

actors, somewhere in the desert, like NAZARIN,

he managed to create a masterpiece. When he had a reasonable budget, the result

was not exactly the same. Maybe we share the same kind of imagination. My imagination

is too strong to completely abandon what is important to me. Also, I don't think

I am a universal director. I don't think I could direct comedies, for example.

I simply cannot escape from myself. I have to fight with the money, that's better

for me, that's the type of cinema I grew up with. The difficulties I encounter

during production oblige me to invent, to become really creative. I think it's

in these moments that my cinematic universe becomes a reality. Anything else

would be dishonest and a waste of time and energy.

Le Frisson des Vampires

was heavily influenced by the trappings of the Hippie movement.

![]() To

a certain extent, yes. I thought it would be nice to work that in. I liked the

music of the group Acanthus very much. Jean-Phillipe Delamarre, the brother

of my assistant Jean-Noelle, had a little music publishing company. One day,

he told me that there were these young schoolboys who had formed a group and

liked the fantastic cinema, and that they wanted to work with me. That's how

we got together. They separated right after and never did anything else again.

They disappeared.

To

a certain extent, yes. I thought it would be nice to work that in. I liked the

music of the group Acanthus very much. Jean-Phillipe Delamarre, the brother

of my assistant Jean-Noelle, had a little music publishing company. One day,

he told me that there were these young schoolboys who had formed a group and

liked the fantastic cinema, and that they wanted to work with me. That's how

we got together. They separated right after and never did anything else again.

They disappeared.

What about the film's leading actress, Sandra Julien?

She was incredibly beautiful...

![]() ...

and not too clever, I must tell you [LAUGHS]! She was a model and, you're right,

very beautiful. She also appeared in a couple of other French films at that

time. We were looking for a girl to play the leading part, which was not exactly

easy. It was a vampire film with erotic scenes, and that didn't sound particularly

enticing to a lot of actresses. I worked with Sandra's husband, Pierre Julien,

who was a technician on Le Frisson... and

Jeunes Filles Impudiques ("Young Girls Without

Shame," 1973), a sex film I did few years later. He suggested Sandra, we made

a screen test and she was perfect.

...

and not too clever, I must tell you [LAUGHS]! She was a model and, you're right,

very beautiful. She also appeared in a couple of other French films at that

time. We were looking for a girl to play the leading part, which was not exactly

easy. It was a vampire film with erotic scenes, and that didn't sound particularly

enticing to a lot of actresses. I worked with Sandra's husband, Pierre Julien,

who was a technician on Le Frisson... and

Jeunes Filles Impudiques ("Young Girls Without

Shame," 1973), a sex film I did few years later. He suggested Sandra, we made

a screen test and she was perfect.

|

|

|

![]() Something

very funny happened during the shooting of that scene. The motorway passes that

cemetery up on a hill and we checked to see if motorists might see what was

going on down there. There was some sort of fence, so we figured they couldn't

see, so we started filming. What we didn't take into account was the elevation

of trucks. The truck drivers could see everything! During the shooting, we looked

up by accident and there was this incredible traffic jam, with countless trucks

backed up on the motorway to enjoy the show!

Something

very funny happened during the shooting of that scene. The motorway passes that

cemetery up on a hill and we checked to see if motorists might see what was

going on down there. There was some sort of fence, so we figured they couldn't

see, so we started filming. What we didn't take into account was the elevation

of trucks. The truck drivers could see everything! During the shooting, we looked

up by accident and there was this incredible traffic jam, with countless trucks

backed up on the motorway to enjoy the show!

I wonder why these extra scenes were not used for

other world markets. It's obviously more commercial--more sex, more violence.

![]() Yes,

but the censorship in France was very strict at that time. And honestly, the

film didn't need them. What we had was enough and I didn't want that stuff to

be put in. I don't like it. I don't know what became of this material. Maybe

it is in the lab, but I doubt it. I guess it is destroyed. Not much of a loss

if you ask me. Monique Natan, the producer of the film, wanted to produce another

vampire film with Sandra Julien immediately afterwards, called Docteur

Vampire ("Dr. Vampire"). That title was her idea and she announced

it, so nobody else could use it. I was supposed to write a script but unfortunately,

she died before the project could become a reality.

Yes,

but the censorship in France was very strict at that time. And honestly, the

film didn't need them. What we had was enough and I didn't want that stuff to

be put in. I don't like it. I don't know what became of this material. Maybe

it is in the lab, but I doubt it. I guess it is destroyed. Not much of a loss

if you ask me. Monique Natan, the producer of the film, wanted to produce another

vampire film with Sandra Julien immediately afterwards, called Docteur

Vampire ("Dr. Vampire"). That title was her idea and she announced

it, so nobody else could use it. I was supposed to write a script but unfortunately,

she died before the project could become a reality.

Tell me something about the history of Requiem pour

un Vampire, one of your most successful films.

![]() During

the shooing of Le Frisson..., I met Lionel

Wallmann. He was an American in charge of selling the film to foreign countries.

We became friends, and he asked me, "Why don't we try to raise the money for

a film together?" I wrote a screenplay, he found money and arranged something

with Sam Selsky. The result was Requiem...,

a little film made with almost no money. I like it very much, because I tried

something different. I think there is no dialogue in the film for the first

40 minutes; I wanted to create the ultimate nave film, to simplify story, direction,

cinematography, everything. Like a shadow, an idea of a plot. Later, I made

an even more extreme film in that mode, called La Rose

de Fer ("The Iron Rose," 1972). I wanted to make a film that was

like a fairy tale told by someone at a campfire, invented as it was being told.

I wrote the script without a plan, without construction, and that's also the

way I shot it.

During

the shooing of Le Frisson..., I met Lionel

Wallmann. He was an American in charge of selling the film to foreign countries.

We became friends, and he asked me, "Why don't we try to raise the money for

a film together?" I wrote a screenplay, he found money and arranged something

with Sam Selsky. The result was Requiem...,

a little film made with almost no money. I like it very much, because I tried

something different. I think there is no dialogue in the film for the first

40 minutes; I wanted to create the ultimate nave film, to simplify story, direction,

cinematography, everything. Like a shadow, an idea of a plot. Later, I made

an even more extreme film in that mode, called La Rose

de Fer ("The Iron Rose," 1972). I wanted to make a film that was

like a fairy tale told by someone at a campfire, invented as it was being told.

I wrote the script without a plan, without construction, and that's also the

way I shot it.

What about your use of symbols? Clowns, for example,

appear quite often in your films--in La Rose de Fer,

Requiem... and Les Demoniaques--yet I don't think

you have a special affection for the circus.

![]() No,

not in particular. These are just ideas, images which represent an emotion.

I also put them into my films to add an element of the strange and absurd. It's

like a mask. For Requiem..., I had some

ideas and put them in the screenplay for no special reason. First the clowns,

then the motorcycle, and the idea of the girls playing piano in the cemetery.

The first vision I had was two clowns playing piano in a cemetery. I have never

seen that in a film before and I wanted to see it, so I just wrote it

in. Afterwards, I reused the image of the clowns in other films as some sort

of quotation. I like that; I often make references to my earlier films. It connects

dreams and stories like a construction system and the audience can make their

own thing out of it.

No,

not in particular. These are just ideas, images which represent an emotion.

I also put them into my films to add an element of the strange and absurd. It's

like a mask. For Requiem..., I had some

ideas and put them in the screenplay for no special reason. First the clowns,

then the motorcycle, and the idea of the girls playing piano in the cemetery.

The first vision I had was two clowns playing piano in a cemetery. I have never

seen that in a film before and I wanted to see it, so I just wrote it

in. Afterwards, I reused the image of the clowns in other films as some sort

of quotation. I like that; I often make references to my earlier films. It connects

dreams and stories like a construction system and the audience can make their

own thing out of it.

You are talking about very ambitious things, yet your

films were hardly treated seriously, either by audiences or by critics. Weren't

you incredibly frustrated at times? Didn't you feel misunderstood? Just look

at the retitlings of some of your films in certain countries!

![]() Do

you mean CAGED VIRGINS for Requiem

pour un Vampire in the United States, or "Sexual Terror of the Unleashed

Vampires" for Le Frisson... in Germany?

[LAUGHS] I never really understood what audiences thought about my films. Requiem...

was fairly successful here in France. During one screening, I sat in the audience

to listen to what the people said about it. Some just came because of the nudity,

some came because it was a vampire film, and others came because they wanted

to see something unusual and bizarre. There is no typical audience for my films,

and this leaves me in a kind of vacuum. Do you know what I mean? I often had

the impression that I did what I was doing solely for myself.

Do

you mean CAGED VIRGINS for Requiem

pour un Vampire in the United States, or "Sexual Terror of the Unleashed

Vampires" for Le Frisson... in Germany?

[LAUGHS] I never really understood what audiences thought about my films. Requiem...

was fairly successful here in France. During one screening, I sat in the audience

to listen to what the people said about it. Some just came because of the nudity,

some came because it was a vampire film, and others came because they wanted

to see something unusual and bizarre. There is no typical audience for my films,

and this leaves me in a kind of vacuum. Do you know what I mean? I often had

the impression that I did what I was doing solely for myself.

![]() As

far as retitlings are concerned, certainly it is quite embarrassing, but there

is nothing I can do about it. I mean, I was happy that one of my films was going

to be shown in another country at all--a sold CAGED

VIRGINS is better than an unsold Requiem

pour un Vampire!

As

far as retitlings are concerned, certainly it is quite embarrassing, but there

is nothing I can do about it. I mean, I was happy that one of my films was going

to be shown in another country at all--a sold CAGED

VIRGINS is better than an unsold Requiem

pour un Vampire!

Is it true that Lionel Wallmann was responsible for

your attempts at straight sex fare with Jeunes Filles

Impudiques?

![]() That's

right. Lionel obliged me to put some sex scenes in Requiem...

during the dungeon sequence. I told him that I wasn't too fond of that kind

of thing, and he answered: "But you do that kind of thing very well. If we made

an entire film like that, I bet it would be successful. You may not like it,

but you know how to do it."

That's

right. Lionel obliged me to put some sex scenes in Requiem...

during the dungeon sequence. I told him that I wasn't too fond of that kind

of thing, and he answered: "But you do that kind of thing very well. If we made

an entire film like that, I bet it would be successful. You may not like it,

but you know how to do it."

![]() I

said, "Okay, I'll do it, but I won't invest any of my own money into it." Well,

he raised the money, we made the film, and he was right. The two sex films I

made, this one and Tout le Monde il en a Deux

(1974) were very successful.

I

said, "Okay, I'll do it, but I won't invest any of my own money into it." Well,

he raised the money, we made the film, and he was right. The two sex films I

made, this one and Tout le Monde il en a Deux

(1974) were very successful.

Tout le Monde... was

later reissued under the title Bacchanales Sexuelles

with hardcore inserts. Did you direct these scenes?

![]() I

have never seen this version, so I don't know what scenes were in it. I never

shot any hardcore scenes for that film, but we went to the very limit of softcore

because Lionel wanted to have something really spectacular and porno wasn't

legal at that time. We did two different versions of the film. For one, which

was eventually released as Tout le Monde...,

I cut out certain scenes which I considered too long, or a bit too explicit.

Thus, I don't know if this reissue is simply the original cut, or a version

spiced-up with real hardcore inserts filmed by someone else. Should the latter

be the case, I don't have anything to do with it.

I

have never seen this version, so I don't know what scenes were in it. I never

shot any hardcore scenes for that film, but we went to the very limit of softcore

because Lionel wanted to have something really spectacular and porno wasn't

legal at that time. We did two different versions of the film. For one, which

was eventually released as Tout le Monde...,

I cut out certain scenes which I considered too long, or a bit too explicit.

Thus, I don't know if this reissue is simply the original cut, or a version

spiced-up with real hardcore inserts filmed by someone else. Should the latter

be the case, I don't have anything to do with it.

It is said that had a lot of problems on Les

Demoniaques because it was a Belgian coproduction.

![]() We

had to change everything because of that. We had to get Belgian actors and technicians.

It was our first co-production and my largest budget up to that time. Even with

the Belgian money involved, we were close to leaving it unfinished. There was

one week of shooting ahead of us, and we had absolutely no money left. We were

in despair and really didn't know how to go on. So, we all went into a little

bar where the director of photography got drunk every night. They were selling

lottery tickets there, and that night, they had only one ticket left. Lionel

bought it, just for fun, and he won about 100,000 Francs! We were saved!

We

had to change everything because of that. We had to get Belgian actors and technicians.

It was our first co-production and my largest budget up to that time. Even with

the Belgian money involved, we were close to leaving it unfinished. There was

one week of shooting ahead of us, and we had absolutely no money left. We were

in despair and really didn't know how to go on. So, we all went into a little

bar where the director of photography got drunk every night. They were selling

lottery tickets there, and that night, they had only one ticket left. Lionel

bought it, just for fun, and he won about 100,000 Francs! We were saved!

![]() But

that's only one story. I had terrible problems, because during the first week

of shooting, Lionel, who was producing for his company Nordia Film, stayed in

Paris to check the rushes, which we sent him from the little island where we

were shooting. We booked a little castle on the island, which belonged to Louis

Renault of the automobile company. There were numerous free rooms and an old

keeper and we stayed there for the whole time. After Lionel saw the rushes,

he rushed to the island immediately and said that everything we had done so

far was absolutely dreadful and unusable, and that we would have to shoot everything

again! I was very disappointed and I didn't understand what was going on. So

there I was, sitting on this island, feeling the pressure of having turned the

efforts of an entire week into unusable crap. When I finally saw the rushes

myself, I was quite surprised, because everything was fine and perfectly usable.

It was exactly what I wanted! Lionel didn't understand the difference between

rushes and finished film, and so he learned the importance of adding sound and

music.

But

that's only one story. I had terrible problems, because during the first week

of shooting, Lionel, who was producing for his company Nordia Film, stayed in

Paris to check the rushes, which we sent him from the little island where we

were shooting. We booked a little castle on the island, which belonged to Louis

Renault of the automobile company. There were numerous free rooms and an old

keeper and we stayed there for the whole time. After Lionel saw the rushes,

he rushed to the island immediately and said that everything we had done so

far was absolutely dreadful and unusable, and that we would have to shoot everything